How widow was inspired to fund research into brain tumours

It’s a funny thing grief.

For three years after the death of her husband Peter, Pam Roberts admits she put up the barriers. To the outside world, even some of her closest friends and family, she appeared to have found a new strength as she adjusted to life without her childhood sweetheart.

“I was the greatest actress RADA never had,” says Pam, who was in her mid 50s when she lost Peter. “I went onto autopilot, but eventually I knew I had to go on living. I needed a focus.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome might have found a new hobby, moved house or taken up volunteering. Pam, however, went a little further. She decided she was going to raise £1m to fund research into the type of brain tumour which had killed her husband and many others like him.

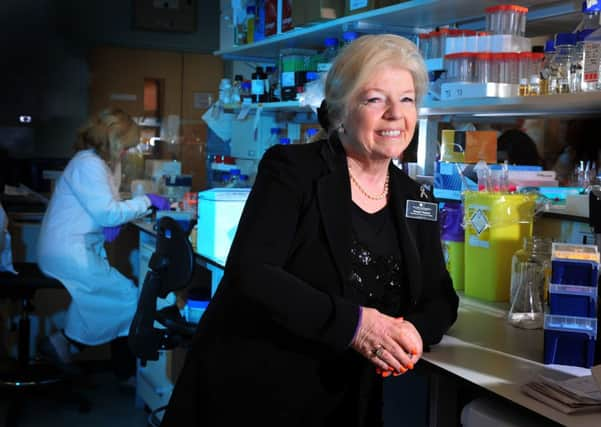

Pam had no experience of running a charity, but she had determination in spades and five years on she, along with a dedicated group of volunteers who she has recruited along the way, has just reached the halfway point.

For the last three years, the charity, which began on her kitchen table in Ripley, has funded a research post at the University of Leeds’ Institute of Cancer and Pathology. The laboratory, based at the city’s St James’ Hospital, opened in 2011 and while relatively new it is fast emerging as a centre of excellence

“You do have to work hard to get people to take you seriously,” says Pam, looking back over the last five years. “Fortunately I already had a good relationship with the team which had looked after Peter and I just knew that there was an opportunity to make a real difference.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe prognosis for those diagnosed with the likes of leukaemia and breast cancer have improved markedly over the last two decades. That trend is largely down to the amount of money invested in research and treatments. It’s something the area of brain tumours has traditionally lacked, so when Pam refers to it as a forgotten cancer it’s with good reason.

“The brain tumour research group is only a few years old, but it’s grown relatively quickly and a lot of that is to do with Pam,” says Professor Susan Short, who leads the team at the institute “Something like breast cancer has attracted large amounts of funding partly because people are so aware of the condition.

“The problem with brain tumours is that sadly there aren’t many survivor stories. Without people talking about a disease it often stays in the shadows when it comes to investment. Those with tumours are often diagnosed late because the brain can keep functioning with a pretty large amount of malignant material. By the time symptoms begin to show the tumour is often quite big, very difficult to remove and the prognosis quite bleak.

“Unlike many other cancers there is no lifestyle factors involved. It’s not related to whether you smoke or what your diet is like. It’s a cancer which is completely arbitrary.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe centre is currently looking at a new type of drug which may stop the cancer cells moving through the brain, which is one of the key reasons why tumours are so difficult to treat. If it proves possible to stop the cells from being so mobile then the outcome for patients may be significantly better than it is now.

Reaching the landmark half million pound mark means the PPR Foundation has been able to renew the research scientist contract for another three years, along with a laboratory technician and research nurse.

Key to finding better ways of treating brain tumours is the availability of donated tissues and part of the role of the foundation-funded research nurse is to talk to suffers and their families about donating tissue.

“No one asked Peter or I whether he would want to donate tissue to research. If they had, I am sure the answer would have been ‘yes’. When I first started working with the team at Leeds, they only had access to quite old tissue, but the appointment of the research nurse has made a real difference.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“If the tissue isn’t used for research it ends up in the incinerator. It’s as simple as that and a lot of people in Peter’s position want to help. They know any developments are too late to help them, but they also know it may prevent other families from facing the very worst case scenario.”

When it became clear that Peter’s time was short, Pam, who lives in Ripley, says they pushed the fast forward button.

“Peter was a successful businessman and had been able to retire at 55,” she says. “We had been looking forward to so many things, but the following year he was diagnosed with the brain tumour. We never stopped that first 12 months and we managed to create some really happy memories. However, gradually the disease took hold and Peter’s world became smaller and smaller.

“Brain tumours affect cognitive ability and for me it was like Peter had early onset dementia. His behaviour was often bizarre and I described it as him living in Peter’s Land. As the disease progressed, he would become fixated on things.

Advertisement

Hide Ad